Family court disputes involving children are among the most difficult and challenging cases that any litigant (i.e., a person who takes their case to court) can face. They are challenging for family lawyers and judges, too. This is because emotions naturally run high, and the stakes – the future of a parent’s contact with the child – run even higher.

Whether you’re at the start of proceedings or caught in a long-standing dispute, understanding how the family court assesses children’s disputes is essential. Below, we have outlined what you need to know about the process.

1. What is a Child Contact Dispute?

These disputes generally fall into two categories.

The first category involves disagreements about who a child should live with or the pattern of contact. For example, the mother might say that the child should live with her and spend every other weekend with the father, whereas the father might say that the child should live equally with both parents on an alternating weekly basis.

The second and most serious category is where the resident parent (i.e., the parent with whom the child is living) completely blocks contact between the child and the other parent. In such cases, there are often allegations of domestic abuse, parental alienation, or other allegations about the child’s welfare. The path to resolution in these cases is usually long and complex because the court may want to have a hearing to decide whether the allegations being made are true.

2. Before applying: mediation

The first formal step is usually attendance at a Mediation Information and Assessment Meeting (MIAM). This is a mandatory requirement in that you must comply with it before any application is made to the family court, unless an exemption applies.

Exemptions apply where, for example, the other parent has made allegations of domestic abuse or if there is exceptional urgency. If mediation is unsuitable because there is an applicable exemption or unsuccessful because the parties do not agree, then the next step is to apply to the Family Court.

3. Taking the First Step: Applying to Court

This is usually done via a form C100, which can be completed in PDF format or online. In response, the court will list (meaning schedule) a first hearing (also known as a First Hearing Dispute Resolution Appointment or a “FHDRA”). At this stage, the court will ask “Cafcass” to speak to the parents and give an initial view to the court in the form of a letter.

Cafcass (the “Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service”) is an independent public body, the primary role of which is to safeguard and promote the welfare of children involved in family court proceedings. Cafcass advises the courts on what is in the best interests of each child and – in theory – does not discriminate between mothers and fathers.

After receipt of the initial Cafcass letter, the parties should be ready for the first hearing (the FHDRA).

4. What happens at each hearing (the procedure in court)

The direction that family court proceedings take depends heavily on whether domestic abuse is alleged.

Route 1: no domestic abuse alleged

If domestic abuse is not alleged, or the allegations relate to relatively minor incidents, then the family court proceedings may end relatively quickly with two or three hearings, including the first hearing. In such cases, the court at the first hearing usually asks Cafcass to complete a full welfare report on the child.

The Cafcass report will contain recommendations on the child’s living arrangements and whether (and if so what) contact should take place between the child and the applying parent.

After Cafcass completes the full welfare report, a second hearing takes place. This is called a Dispute Resolution Appointment or “DRA”. In many cases, the parents, having read the Cafcass report, reach agreement at this second “DRA” hearing. If no agreement is reached, then the court lists (schedules) the case for a final hearing.

The court usually asks the Cafcass officer who wrote the report to attend the final hearing to give evidence. This means that, if a parent disagrees with the recommendations in the report, then they may challenge the recommendations by having their family law barrister question the Cafcass officer. After hearing evidence from the parents and Cafcass, the court makes a decision.

Route 2: domestic abuse alleged

If serious domestic abuse is alleged, then the proceedings become much more complex. In such cases, the court will want to have a hearing to decide whether the allegations being made are true. These hearings are known as fact-finding hearings. For a deeper look at fact-finding hearings, see our article What happens in a Family Court fact-finding hearing?

Whatever the outcome at the fact-finding hearing, i.e., whether the allegations are found to be proved or not proved, the findings made by the judge are relayed to Cafcass, to enable it to write a welfare report. The process then reverts back to the “route 1” process described above, with a final hearing being listed after the Cafcass report becomes available.

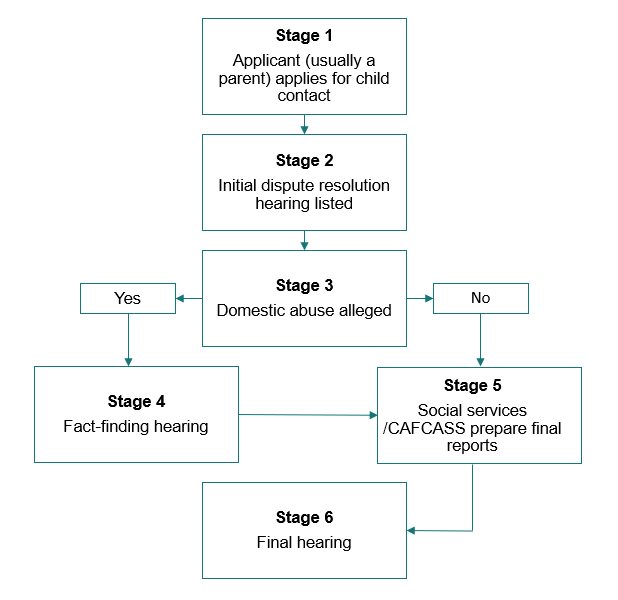

The process in summary is as follows:

5. Facing allegations of domestic abuse

If you are facing allegations of domestic abuse, then you must take these allegations seriously, even if you believe that they are completely false. This is because, if the family court decides that the allegations are proven, then the court will, for the remainder of the proceedings, act as though the abuse actually happened.

The family court operates a “binary system” whereby the incidents underlying allegations of domestic abuse either:

- happened; or

- did not happen.

This was summarised by the House of Lords (the old name for what is now the Supreme Court) in Re B (Care Proceedings: Standard of Proof)[2008] UKHL 35 as follows:

“[i]f a legal rule requires a fact to be proved (a “fact in issue”), a judge or jury must decide whether or not it happened. There is no room for a finding that it might have happened. The law operates a binary system in which the only values are 0 and 1. The fact either happened or it did not. If the tribunal is left in doubt, the doubt is resolved by a rule that one party or the other carries the burden of proof. If the party who bears the burden of proof fails to discharge it, a value of 0 is returned and the fact is treated as not having happened. If he does discharge it, a value of 1 is returned and the fact is treated as having happened.”

The consequences of allegations being proven in such a binary system can be severe. In many cases, the findings of domestic abuse lead to the court effectively ordering that there be no contact between the “abusing” parent and the child.

The law’s binary approach to fact-finding may feel blunt, but it’s deliberate; the thought process behind the binary approach is that uncertainty cannot govern a child’s future; the court needs to establish a view of events. For parents involved in the family court process, the fundamental question is this: “will the court find the truth of the matter?”.

6. The court’s approach at the final hearing

The Welfare Checklist in section 1(3) of the Children Act 1989 is a fundamental tool used by the family court when it makes decisions in a children case. The checklist sets out a series of specific factors that the court must consider whenever it is determining what living arrangements best serve the welfare of a child.

The checklist contains the following considerations:

- “The wishes and feelings of the child” (taking into account the child’s age and understanding). This does not mean that the child gets to decide, but it does mean that their voice matters.

- “The child’s physical, emotional and educational needs”: this includes matters such as stable housing, psychological wellbeing, and schooling.

- “The likely effect of any change in circumstances”: this includes considerations such as how a move between homes might affect the child’s routine or sense of security.

- “The child’s age, sex, background and any relevant characteristics”: this includes consideration of the child’s cultural background, religion, language, or disability.

- “Any harm the child has suffered or is at risk of suffering”: this includes not just physical harm, but also emotional or psychological harm. Any findings of domestic abuse made at the fact-finding stage will feature heavily in this category.

- “How capable each parent is of meeting the child’s needs”: this entails an assessment of each parent’s capabilities as a parent, both emotionally and practically.

This checklist embodies the core principle of the 1989 Act: that the child’s welfare is paramount. However, rather than leaving that core principle vague, the checklist creates a solid structure within which the principle operates. In this way, an abstract principle becomes a practical decision-making framework. Understanding how this checklist works can help you to prepare your case effectively.

7. What if things go wrong? Can I appeal a decision of the family court?

You can possibly appeal a decision of the family court – it depends on whether you have a proper reason to do so.

It is important to understand that appeals aren’t just about disagreeing with the decision. To succeed on appeal, you must show that the judge made a legal or procedural error, or reached a decision that was wrong based on the evidence. For example, the court might have misunderstood important facts, failed to apply the law correctly, or not given clear reasons for its decision.

It’s also worth noting that appeals aren’t a “second go” at the case. The appeal court is highly unlikely to allow new evidence to be presented at the appeal stage. The appeal court will focus on how the original decision was made, and not on whether it (the appeal court) would have come to a different conclusion from the original court.

In short, an appeal is a legal scalpel, which is reserved for cutting through errors, not for reopening wounds.

If you’re unhappy with the family court’s decision, then you should get expert advice quickly because the time-limit for appealing is usually 21 days from the date of the decision. A barrister experienced in family law can assess whether you have realistic grounds for appeal and guide you through what is a complex appeal process.

For a more technical look at family court appeals, see our article Can you appeal against a decision of the Family Court .

8. Getting help from a direct access barrister (and is it cheaper than working with a solicitor?)

Instructing a direct access barrister allows you to tap into expert legal support without needing to go through a solicitor. This means that you can go straight to the person who will be representing you in court. As a specialist advocate, a barrister:

- can provide strategic legal advice from the outset of your case

- draft clear and persuasive documents, such as witness statements or position statements (this is a fundamental part of the process – the courtroom is not the place to find out whether your documentation is good enough. A direct access barrister can help to ensure that it is – before it ever reaches the judge’s desk).

- is skilled in both oral advocacy, i.e., in presenting cases in court, for example, in directions hearings, fact-finding hearings, final hearings or appeal hearings.

The direct access model offers not only access to the barrister’s expertise, but also cost-efficiency and flexibility. You can instruct a barrister just for the elements you need, whether that’s a one-off piece of drafting, help preparing for a hearing, or full representation in court. This targeted approach can significantly reduce your overall legal costs compared to instructing a solicitor and barrister team.

Contact Demstone Chambers

Demstone Chambers are direct access barristers specialising in family law, including children disputes and divorce-related matters. We are able to help clients with almost every aspect of children related disputes, including advising generally, drafting documents and appearing in court.

This article is subject to the terms of our website disclaimer